The deformed is always inharmonious with the divine, and the beautiful harmonious.” – Socrates

This quote comes from a belief that exposure to beauty will improve us, and ugliness will degrade us, or that ugliness is a punishment. Even today, people will attach morals to what is deemed as “ugly”, whether it is justified or not. This is easy to see with people: “ugly” people with culturally “unattractive” features will be made into villains, whereas the heroes of stories must always be beautiful – or end up beautiful in the end. But this is also prevelant in space and architecture. And there is no greater examples than prisons.

Architecture:

Prison architecture is brutalistic – thick concrete walls, solid square and rectangle shapes, and minimal, cold aesthetics. This is partly because of the origins of a prison not being the punishment itself, but being a holding place for criminals who would later be executed, but it is also partly because prison did become a punishment in of itself, and punishment is not supposed to be pleasant. So in doing so, prison designs become quite unhumane. Cells have a plainness that emphasise exclusion and loss, and activities are put in a setting that emphasises social stigma and untrustworthiness – no decoration, only penal functionality. It is teaching, however subtley, that beauty is only reserved for the good and moral, and must be earned. This idea even goes beyond the architecture and weaves its way into every aspect of prison life: unappetizing food, course and ugly clothing, featureless and comfortless rooms, drudging and unrewarding work.

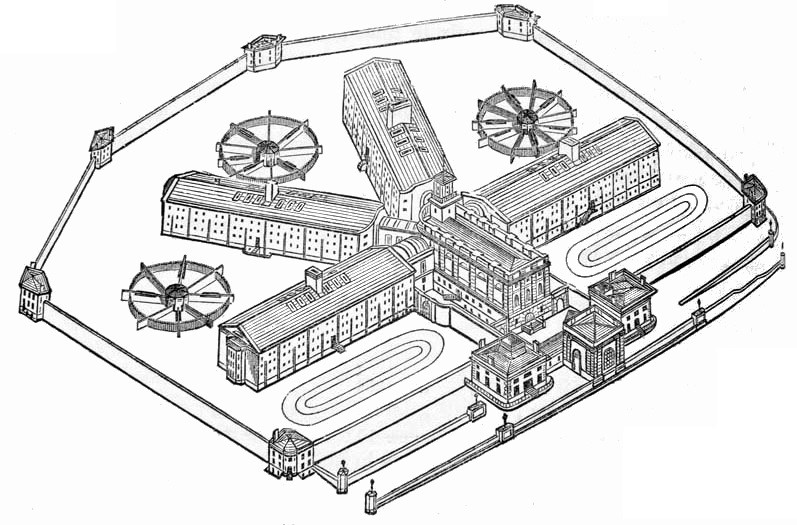

Despite prisons being reputable for being harsh and featureless, even they had trends that reflected the cultural, political, and business climate. In the 19th century, prisons were made of stone and built like fortresses, demonstrating the might of the state. Then the “seperation system” came into effect, with designs such as Pentonville Prison and the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philidelphia prioritising isolation with back-to-back interior cellhouses arranged into tiers and enveloped into enormous blocks, with the goal of encouraging reflection for rehabilitation. Incidentally, this is also about the time the “Panopticon Prison” idea was first drafted.

An isometric drawing of Pentonville prison, from an 1844 report by Josua Jebb, Royal Engineers.

Now in the modern day, there are still calls for prisons to become more humane to encourage participation in re-socialising activities and to reduce emotional, mental, and physical abuse.

For example, Storstrøm Prison in Denmark is designed almost like a heavily monitored University campus, with “units” consisting of shared kitchens and living spaces with a for inmates to prepare their own meals, to encourage regular living habits while incarcerated. Each individual cell, 4-7 per unit, comes with its own fridge, TV, wardrobe, and a large window. A colour palette of blue and orange was selected to reduce the feeling of an institution, with integrated artwork and natural lighting and views of the Danish countryside. This creates a healthier living environment. Additionally, as it is a relatively small facility, staff members can better respond to individual needs, and reduce levels of isolation and anxiety.

However, for designs such as these, there are practical limitations like cost and incarceration rates: Denmark has a much lower population than countries such as the USA or China, and therefore less prisoners.

Function:

The function of a prison is actually fairly complex, because prisoners must remain incarcerated without having any of their human or civic rights broached. This means that food, clothing, services, and accomodation must meet regulation. However, there are frequent lapses in this, as prison design and construction are usually given low priority due to hostile attitudes to offenders, with the idea that the squalor and danger of a prison can serve as a deterrent from lawbreaking, and those who find themselves in prison “deserve” these conditions.

Also, principles such as efficiency, economy, security, and control, dictate that prison design must be uniform in provisions – so cells must be identical, and the furniture, layout, lighting, heating, and ventilation must be identical. To avoid vandalism and carelessness, the buildings, equipment, and aesthetics have to be simple and durable. And since the pace of incarcaration is on the rise, prisons have to be built at an astonishing rate, so they have been standardized in architecture and design to allow swift and economic construction. On the security front, there must be barriers to prevent escape, and the prison must be compartmentalized into sectors so prisoners have a hard time moving room to room, and the staff must have clear sightlines for escapees; access to staff offices, facilities, and vantage points must also be denied or restricted.

The functionality of a prison also depends on how big the prison is. Smaller ones can delegate more freedom of movement and large groups of people with recreation grounds and workshops – less people to keep an eye on means more flexibility. On the other hand, super-maximum prisons will allow little to no freedom; prisoners will have few places outside of their cells and will not be allowed in large groups, with more remote communication and a high level of seperation between inmate and staff.

Fairweather, L. and McConville, S., 2013. Prison architecture. Routledge.

My Game:

In my mind, I always imagined what the Watched are escaping from was a prison – it was inspired by a Panopticon, which originated as a prison, and the high levels of security, isolation, and the aesthetic became more and more prison-like as I explored the concept. This has definitely given me some alternative ideas to how I should structure my gameworld, other than “tower”.

Leave a Reply