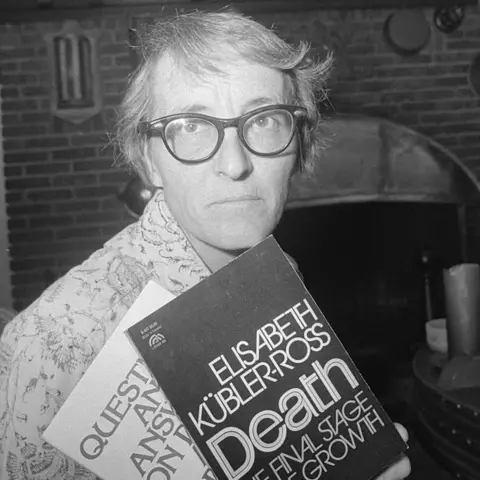

My main reference for this research was derived from the 2023 publication Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief (Tyrrell et al., 2023).

Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross introduced the most commonly taught model for understanding the psychological reaction to imminent death in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. The book explored the experience of dying through interviews with terminally ill patients and outlined the five stages of dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Her work marked a cultural shift in the approach to conversations regarding death and dying as prior to this, the subject of death was somewhat taboo, either talked around or avoided altogether.

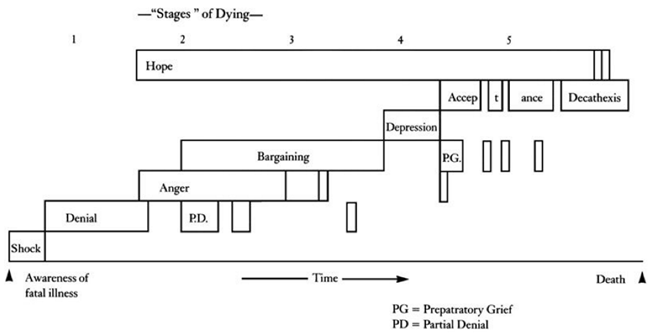

Interestingly, there were never just five stages. While each of the stages do get their own chapter, a graphic in the book describes as many 10 or 13 stages, including shock, preparatory grief – and hope. The diagram below depicts clearly how the stages aren’t linear.

Kübler-Ross and others applied the model to the experience of loss in many contexts, including grief and other significant life changes. Initially the stages were frequently interpreted strictly, an expectation that patients would pass through the stages in sequence, however she noted that individual patients could manifest each stage differently, if at all.

“The five stages are meant to be a loose framework – they’re not some sort of recipe or a ladder for conquering grief. If people wanted to use different theories or different models, she didn’t care. She just wanted to begin the conversation.”

– Ken Ross, Dr. Kübler-Ross’ son

Understanding the patterns and emotions associated the process of grievance was said to help health care providers provide empathy and understanding to patients, families, and team members to ease confusion and frustration (Rothweiler and Ross, 2019).

Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Dying

| Denial | Common defence mechanism used to protect oneself from the hardship of considering an upsetting reality. Kübler-Ross noted that patients would often reject the reality of the new information after the initial shock of receiving a terminal diagnosis. Patients may directly deny the diagnosis, attribute it to faulty tests or an unqualified physician, or simply avoid the topic in conversation. While persistent denial may be deleterious, a period of denial is quite normal in the context of terminal illness and could be important for processing difficult information. In some contexts, it can be challenging to distinguish denial from a lack of understanding, highlighting that upsetting news should always be delivered clearly and directly. |

| Anger | Commonly experienced and expressed by patients as they concede the reality of a terminal illness. It may be directed at blaming medical providers for inadequately preventing the illness, family members for contributing to risks or not being sufficiently supportive, or spiritual providers or higher powers for the diagnosis’ injustice. Anger may also be generalised and undirected, manifesting as a shorter temper or a loss of patience. |

| Bargaining | Typically manifests as patients seeking some measure of control over their illness. The negotiation could be verbalised or internal and could be medical, social, or religious. The patients’ proffered bargains could be rational, such as a commitment to adhere to treatment recommendations or accept help from their caregivers. |

| Depression | Perhaps the most immediately understandable of Kübler-Ross’s stages, and patients experience it with unsurprising symptoms such as sadness, fatigue, and anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure). While the patient’s actions may potentially be easier to understand, they may be more jarring in juxtaposition to behaviours arising from the first three stages. |

| Acceptance | Describes recognising the reality of a difficult diagnosis while no longer protesting or struggling against it. Patients may focus on enjoying the time they have left and reflecting on their memories. They may begin to prepare for death practically by planning their funeral or helping to provide financially or emotionally for their loved ones. It is often portrayed as the last of Kübler-Ross’s stages and a sort of goal of the dying or grieving process. |

Criticisms

While the model has both historical and cultural significance as one of the most well-known models for understanding grief and loss. The principal criticisms of the stages of death and dying are that the stages were developed with insufficient evidence and are applied too strictly.

Critics have focused on the fact that the concept of “stages” is applied too rigidly and linearly. Criticism started when the stages were viewed more literally, indicating that a patient must move through each stage to reach the final goal of “acceptance.” This view also assumes that progression through the stages is linear and that some stages are inherently less adaptive than others. Dr. Kübler-Ross and others have reminded readers that many patients will experience the stages fluidly, often exhibiting more than one at a time and moving between them in a non-linear fashion.

“People who don’t go through these stages – and as far as I can tell that’s most people – can be led to believe that they are grieving incorrectly,”

– Professor George Bonanno

In terms of little evidence for the stages – the most extensive study was published in 2007. The study was based on a series of interviews with recently bereaved people. It concluded that although Kübler-Ross’s stages were present in different combinations, the most prevalent emotion reported at all stages was acceptance. Denial (or disbelief, as the study termed it) was very low, and the second strongest emotion reported was “yearning”, which was not one of the original five stages (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block and Prigerson, 2007). This study has been criticised, though, for selective sampling and overstating its findings.

However, while academics go back and forth on the matter, various psychologists will continue to back that the grieving people they encounter in their work still find meaning in the theory. The stages help people normalise and rationalise their very valid and often overwhelming emotions.

“Terminally ill people can teach us everything – not just about dying, but about living.

Dr. Kübler-Ross, 1983

So… How does this research apply?

By understanding the emotional progression and learning about the original study (I was surprised to find out it was about terminally ill patients!!!), I will be able to design a game that evokes empathy. By accurately portraying the emotional roller coaster of grief, players will connect more with the protagonist’s journey and perhaps their own. This allows me to structure my game’s narrative around the protagonist’s (or the world’s) evolving emotional state.

Meaningful Symbolism in world-building

Each stage can offer a range of emotional responses that can be symbolised in the game world, aiding in thematic world-building – for example Denial could be represented through illusions or dream-like environments, whereas Anger manifests through destructive and hostile areas. Additionally, interactive storytelling can be incorporated through player choices in their interactions with the five stages, or certain abilities could be unlocked as the protagonist comes closer to accepting the loss. These interactions would create a dynamic connection between the player and the games’s emotional core. The symbolic representations will resonate more deeply with players when grounded in actual research.

Character Development

Research will help me design characters – whether NPCs, allies or antagonists – that reflect or challenge the stages of grief. Each stage aims to present different emotional and psychological aspects for the player to confront, allowing for more nuanced and emotionally engaging interactions.

Mechanics and Gameplay

Research will help me align gameplay mechanics with the emotional challenges of each stage. Each level could embody the struggle of moving through grief. For instance, mechanics like slow movement in Depression could symbolically mirror the emotional heaviness associated with the stage. Similarly, in Denial might involve overcoming illusions or dead ends, reinforcing the theme of avoiding reality.

Leave a Reply